#14: Exclusive Economic Zones & The South China Sea Dispute

Exclusive Economic Zones have been a piece of sovereignty for nation-states since the early 1980s, when they were agreed upon by the United Nations. For many Pacific nations, EEZs play an important role in economic matters as EEZs grant the nation exclusive rights to any material found within the boundary. When a firm like Vestas builds an offshore wind farm or ExxonMobil drills for deepwater oil, they do so only with the permission of the nation in which EEZ the resources lie. This extends to fisheries as well; Ecuador is reliant on its EEZ as it holds a globally significant population of shrimp, the exporting of which is a major contributor to Ecuador’s economy.

EEZs were established for all ocean-bordered nations in 1982 at the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This convention agreed that the EEZ for each nation would be 200nm (370.4km) from the shoreline. Some nations can have EEZs which are larger than their territory; New Zealand’s EEZ is 15x larger on a square-kilometre basis than its landmass due to outlying smaller islands (such as the Kermadecs) generating the same 200nm EEZ as the North & South Islands. The first two nations in the world to declare their EEZs were Peru & Ecuador, each of which declared their exclusive area through a presidential proclamation in 1947. These proclamations were the first to establish 200nm as the extent of the area, which was kept in the formal adoption of EEZs during the Convention on the Law of the Sea.

THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

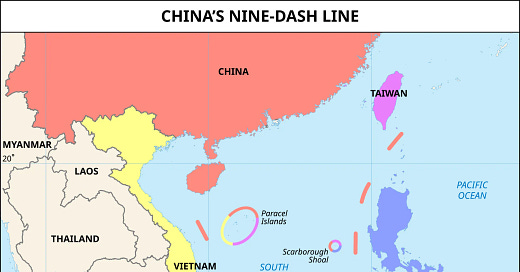

The Convention on the Law of the Sea also established that nations could construct artificial islands within their EEZs, and in doing so, extend their EEZs & sovereignty. These islands are granted rights as provided in standing international law, which has created some tension in the South China Sea. This is an area of the Pacific Ocean with China & Taiwan to its north, Vietnam to its west and Malaysia to its south-west, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei to its south, and the Philippines to its east. Each of these nations claim some area of this body of water for their EEZ, but their claims are all contested by China’s ambitious approach to which island chains it claims.

China’s Nine Dash Line is the origin of these ongoing disputes. This Nine-Dash Line was first presented by the People’s Republic of China (mainland China) in 1947 to areas far to the south of its territory. Within the South China Sea are small island chains, which cannot sustain populations but which can now significantly add to a nation’s EEZ. The most significant island chains are the Paracel Islands & the Spratley Islands. The Paracels are distributed across 15,000 square kilometres of ocean, and the Spratleys are spread across 425,000 square kilometres. China claims these islands and the EEZ which would extend from them.

Both the PRC and Taiwan claim these islands, with Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines rejecting these claims, with them stating this Nine-Dash Line runs contrary to the Convention on the Law of the Sea. The main piece of the conflict seems to be that both the PRC and Taiwan claim the islands from a historical perspective, but that the four Southeast Asian nations go by the UNCLOS. American sources state that this Nine-Dash Line has weak basis in historical fact, while Chinese sources state that current international law cannot override historical fact. A ruling under the UNCLOS’ Permanent Court of Arbitration in a case brought by the Philippines stated that the PRC did not have a legal basis to claim the territory within the Nine-Dash Line as there wasn’t sufficient evidence that their territory had ever stretched that far south in the past.

The headwinds have not stopped the Chinese, nor the Taiwanese or Vietnamese, from constructing artificial islands within the contested body of water. The Vietnamese are especially sensitive to any suggestion of the Nine-Dash Line in media; in 2023 it banned the Barbie film from cinemas as the film briefly has a map with the Nine-Dash Line visible. Something as low-stakes as whether a film is shown in cinemas or not links to a larger picture, one we’ve discussed on this blog before: China’s desire to stretch its muscles in its local region. China is undoubtedly the most powerful nation in this particular neighbourhood, and as emergent powers have always done and will continue to do, it is attempting to remake its local region to benefit itself. This extends to denying smaller parties resources and gaining them for itself, even if the islands & their EEZs in question are of limited use.

When it comes to markets, the Southeast Asian states and China are more or less happy to get along. They compete of course, but each nation knows that economics is not a zero sum game - both parties can benefit from doing business. On matters of sovereignty, the calculus is entirely different: Southeast Asian nations see that if the PRC is given an inch, it will take a mile. The Nine-Dash Line is seen as an erosion of their sovereignty and a part of the trend, with China projecting that an island only 44 kilometres from Malaysia’s shoreline actually belong to it being another prime example.

The Nine-Dash Line was first presented in the 1940s, and only recently has it been mentioned less by Chinese authorities. The effort behind the it is still alive and well; the attempts of a regional superpower to persuade its neighbours to see its point of view, and to chip away at their sovereignty bit by bit. Territorial disputes are always a sore subject (except for the Canadians & Danes and their Whiskey War over Hans Island), and they are slow moving issues to solve. The EEZs are for many nations just that - an area of the oceans which form a critical part of their economic infrastructure, whether its through farming shrimp or extracting petroleum or tourism, etc. For others however, EEZs are a frontline over a war for sovereignty. The Chinese, Taiwanese, Vietnamese, Filipinos, Malaysians, Indonesians, and Bruneians all see their EEZs in this way, and have done for some decades. While this part of the world is only involved in legal battles & lawfare, the length nations will go to to protect their interests & sovereignty could create a flashpoint for an escalation to a real war. As we have seen in Europe, historical claims on territory going back centuries (instead of respect for agreed-upon borders) can be manipulated to the larger power’s advantage.